When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

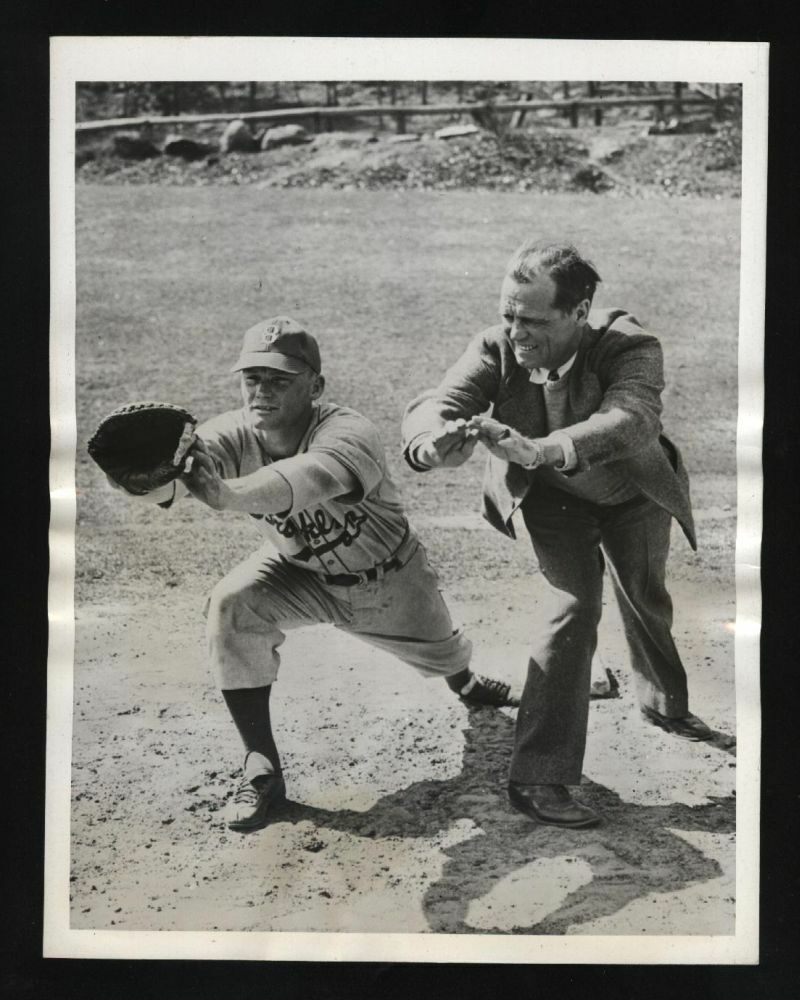

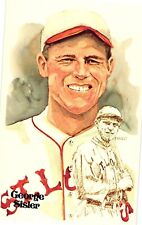

1945 George Sisler VINTAGE Original Photo Hall of Fame Rare measuring approximately 6 5/8 X 8 1/2 inches.

George Sisler was highly thought of as both a person and a ballplayer during his day. A five-tool player before the term came into vogue, Sisler finished his career as one of the game’s greatest hitters.After graduating with a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Michigan in 1915, a rarity for ball-players at the time, Sisler moved right onto the roster of the St. Louis Browns. Starting his career as a pitcher, he eventually became a first baseman in order to get his powerful left-handed bat in the everyday lineup.Peerless defensively at first, Sisler also excelled with his 42-ounce bat in hand. In a big league career that lasted 15 seasons, “Gorgeous George” batted over .300 13 times, including league-leading averages of .407 in 1920 and .420 in 1922. His 257 hits during the 1920 campaign remained a modern major league record until Seattle’s Ichiro Suzuki broke it in 2004. A skilled base runner as well, he led the league in stolen bases four times.Baseball great Ty Cobb, an American League rival for many years, once called Sisler “the nearest thing to a perfect ballplayer” he had ever seen.Sisler claimed that the fact he was once a pitcher helped make him a better hitter. “I used to stand on the mound myself, study the batter and wonder how I could fool him,” he said. “Now when I am at the plate, I can the more easily place myself in the pitcher’s position and figure what is pass-ing through his mind.”At the height of his success as a baseball player, though, he missed the entire 1923 season due to a sinus infection that produced double vision. He would come back to play another seven seasons, hitting .320 during that span, but even he would acknowledge he was never quite the same hitter.Ending his career with 2,812 hits and a .340 batting aver-age, Sisler was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939. But because he often played on second-division teams and never had the national stage of a World Series, he was reserved and much less flamboyant that fellow stars of the time like Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, and as a first baseman was overshadowed by the enormity of Lou Gehrig.George Harold Sisler (March 24, 1893 – March 26, 1973), nicknamed \"Gentleman George\" and \"Gorgeous George\", was an American professional baseball player for 15 seasons, primarily as first baseman with the St. Louis Browns. From 1920 until 2004, Sisler held the Major League Baseball (MLB) record for most hits in a single season; it was broken by Ichiro Suzuki.Sisler\'s 1922 season — during which he batted .420, hit safely in a then-record 41 consecutive games, led the American League in hits (246), stolen bases (51), triples (18), and was probably the best fielding first baseman in the game — is considered by many historians to be among the best individual all-around single-season performances in baseball history.[1]After Sisler retired as a player, he worked as a major league scout and aide. He was on a team of scouts appointed by Branch Rickey to find black players for the Brooklyn Dodgers; the team\'s work resulted in the signing of Jackie Robinson. Sisler was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.[2] In 1999 editors at The Sporting News named him 33rd on their list of \"Baseball\'s 100 Greatest Players.\"Contents 1 Early life

2 Major league career

3 Later life and legacy

4 See also

5 Notes

6 References

7 External linksEarly lifeSisler was born in the unincorporated hamlet of Manchester (now part of the city of New Franklin, a suburb of Akron, Ohio[3]). His paternal ancestors were immigrants from Northern Germany in the middle of 19th century. When he was 14, Sisler moved to Akron to live with his older brother so that he could attend an accredited high school. When Sisler was a high school senior, his brother died of tuberculosis but Sisler was able to move in with a local family and finish school.[4]In 1911, Sisler signed a contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates to play minor league baseball in the Ohio–Pennsylvania League, but he never played in the league or earned any money.[5] He played college baseball for the University of Michigan. As a freshman, Sisler struck out 20 batters in seven innings during a 1912 game.[6] He lettered in baseball from 1913 to 1915.[7] At Michigan he played for coach Branch Rickey and he earned a degree in mechanical engineering.[5]After his graduation from Michigan, Sisler sought legal advice from Rickey about the status of his contract with Pittsburgh. The three-time Vanity Fair All-American had become highly sought-after by major league scouts. Rickey talked to Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss about releasing Sisler from the contract he had signed as a minor, but Dreyfuss maintained his claim to Sisler. Rickey wrote to the National Commission, baseball\'s governing body, who ruled that the contract was illegal. Rickey, now managing the St. Louis Browns, signed Sisler to a contract worth $7,400.[5]

Major league careerSisler entered the major leagues as a pitcher for the Browns in 1915. He posted a career pitching record of 5–6 with a 2.35 earned run average in 24 career mound appearances.[8] He defeated Walter Johnson twice in complete-game victories. In 1916, he moved to first base and finished the season with a batting average above .300 for the first of seven consecutive seasons. He also had 34 stolen bases that season; he stole at least 28 bases in every season through 1922.[8]

1916 D350 George SislerIn 1917, Sisler hit .353, registered 190 hits and stole 37 bases. The next year he hit .341 and stole a league-leading 45 bases.[8] He then enlisted in the army, joining several major league players in a Chemical Warfare Service unit commanded by Rickey. Sisler was preparing to go overseas when World War I ended that November.[9]

George Sisler drawn by Robert Ripley in 1922In 1920, Sisler played every inning of each game.[10] He stole 42 bases (second in the American League), collected a major league-leading 257 hits for an average of .407 and ended the season by hitting .442 in August and .448 in September.[8] His batting average was the highest ever for a 600+ at-bat performance. In breaking Ty Cobb\'s 1911 record for hits in a single season, Sisler established a mark which stood until Ichiro Suzuki broke the record with 262 hits in 2004. (Suzuki, however, collected his hits over 161 games during the modern 162-game season as opposed to 154 in Sisler\'s era.) Sisler finished second in the AL in doubles and triples, as well as second to Babe Ruth in RBIs and home runs.Jim Barrero of the Los Angeles Times asserts that Sisler\'s record was largely overshadowed by Ruth\'s 54 home runs that season. \"Of course, Ruth\'s obliteration of the home run record drew all the attention from fans and newspapermen, while Sisler\'s mark was pushed to the side and perhaps left unappreciated during what was a golden age of pure hitters\", Barrero wrote.[10] As his popularity increased, Sisler drew comparisons to Cobb, Ruth and Tris Speaker. Sisler, however, was much more reserved than those three stars. A writer named Floyd Bell described Sisler as \"modest, almost to a point of bashfulness, as far from egotism as a blushing debutante... Shift the conversation to Sisler himself and he becomes a clam.\"[11]In 1922, Sisler hit safely in 41 consecutive games – an American League record that stood until Joe DiMaggio broke it in 1941. His .420 batting average is the third-highest of the 20th century, surpassed only by Rogers Hornsby\'s .424 in 1924 and Nap Lajoie\'s .426 in 1901. He was chosen as the AL\'s Most Valuable Player that year,[8] the first year an official league award was given, as the Browns finished second to the New York Yankees. Sisler stole over 25 bases in every year from 1916 through 1922, peaking with 51 the last year and leading the league three times; he also scored an AL-best 134 runs, and hit 18 triples for the third year in a row.A severe attack of sinusitis caused him double vision in 1923, forcing him to miss the entire season. He defied some predictions by returning in 1924 with a batting average over .300. Sisler later said, \"I planned to get back in uniform for 1924. I just had to meet a ball with a good swing again, and then run. The doctors all said I\'d never play again, but when you\'re fighting for something that actually keeps you alive – well, the human will is all you need.\"[5] Sisler never regained his previous level of play, though he continued to hit over .300 in six of his last seven seasons and led the AL in stolen bases for a fourth time in 1927.[8]In 1928, the Browns sold Sisler\'s contract to the Washington Senators, who in turn sold the contract to the Boston Braves in May. After batting .340, .326, and .309 in his three years in Boston, he ended his major league career with the Braves in 1930, then played in the minor leagues. He accumulated a .340 lifetime batting average over his 16 years in the majors. Sisler stole 375 bases during his career. He became one of the early entrants elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame when he was selected in 1939.[8]

Later life and legacyAfter his playing career, Sisler reunited with Rickey as a special assignment scout and front-office aide with the St. Louis Cardinals, Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates. Sisler and Rickey worked with future Hall of Famer Duke Snider to teach the young Dodgers hitter to accurately judge the strike zone.[12] Sisler was part of a scouting corps that Rickey assigned to look for black players, though the scouts thought they were looking for players to fill an all-black baseball team separate from MLB. Sisler evaluated Jackie Robinson as a potential star second baseman, but he was concerned about whether Robinson had enough arm strength to play shortstop.[13] With the Pirates in 1961, Sisler had Roberto Clemente switch to a heavier bat. Clemente won the league batting title that season.[14]Sisler\'s sons Dick and Dave were also major league players in the 1950s. Sisler was a Dodgers scout in 1950 when his son Dick hit a game-winning home run against Brooklyn to clinch the pennant for the Phillies and eliminate the second-place Dodgers. When asked after the pennant winning game how he felt when his son beat his current team, the Dodgers, George replied, \"I felt awful and terrific at the same time.\"[15] A passage in The Old Man and the Sea refers to Dick Sisler\'s long home run drives.[14] Another son, George Jr., served as a minor league executive and as the president of the International League.Sisler also spent some time as commissioner of the National Baseball Congress.[16] He died in Richmond Heights, Missouri, in 1973, while still employed as a scout for the Pirates.Outside of St. Louis\' Busch Stadium, there is a statue honoring Sisler. He is also honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[17] In October 2004, Ichiro Suzuki broke Sisler\'s 84 years old hit record, collecting his 258th hit off of Texas Rangers pitcher Ryan Drese. Sisler\'s daughter Frances Sisler Drochelman and other of his family members were in attendance when the record was broken.[18] While in St. Louis for the 2009 All-Star game, Ichiro Suzuki visited Sisler\'s grave site.[19]George Harold Sisler (March 24, 1893 – March 26, 1973), nicknamed \"Gorgeous George\", was an American professional baseball first baseman and player-manager. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the St. Louis Browns, Washington Senators and Boston Braves. He managed the Browns from 1924 through 1926.

Sisler played college baseball for the University of Michigan and was signed by the St. Louis Browns as a free agent in 1915. He won the American League batting title in 1920 and 1922. In 1920 he set the major league record for hits with 257 which stood for 84 years and had a batting average of .407[1] (the seventh highest after 1900). In 1922 he won the AL Most Valuable Player Award, he finished with a batting average of .420 which is the third highest batting average ever recorded after 1900. An attack of sinusitis in 1923 caused Sisler\'s play to decline, but he continued to play in the majors until 1930. After Sisler retired as a player, he worked as a major league scout and aide.

A two time batting champion, Sisler led the league in hits twice, triples twice, and stolen bases four times. He collected 200 or more hits six times in his career, and had a batting average of over .300 a total of 13 times throughout his career. His career batting average of .340 is the 16th highest of all time. Sisler was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.Contents1 Early life2 Major league career3 Later life and legacy4 See also5 References6 External linksEarly lifeSisler was born in the unincorporated hamlet of Manchester (now part of the city of New Franklin, a suburb of Akron, Ohio[2]). His paternal ancestors were immigrants from Northern Germany in the middle of the 19th century. Manchester did not have a high school and when it was time to start, Sisler moved to Akron to live with his older brother so that he could attend school there.[3] Sisler was an athletic student and played baseball, basketball and football[4] in high school, but was more focused on baseball.[4] In 1910, when Sisler was a high school senior, his brother Efbert died of tuberculosis,[5] but Sisler was able to move in with a local family and finish school.[5][6]

In 1911, Sisler signed a contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates to play minor league baseball in the Ohio–Pennsylvania League, but he never played in the league or earned any money[7] and instead played college ball for the University of Michigan. As a freshman pitcher, Sisler struck out 20 batters in seven innings during a 1912 game.[8] He lettered in baseball from 1913 to 1915.[9] At Michigan he played for coach Branch Rickey while earning a degree in mechanical engineering.[7] After he graduated from Michigan, Sisler sought legal advice from Rickey about the status of his contract with Pittsburgh. The three-time Vanity Fair All-American had become highly sought-after by major league scouts. Rickey talked to Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss about releasing Sisler from the contract he had signed as a minor, but Dreyfuss maintained his claim to Sisler. Rickey wrote to the National Commission, baseball\'s governing body, who ruled that the contract was illegal. Rickey, now managing the St. Louis Browns, signed Sisler to a contract worth $7,400 (equivalent to $187,020 in 2019).[7][10]

Major league careerOn June 28, 1915 Sisler made his major league debut, he entered in relief against the Chicago White Sox,[11] he pitched three scoreless innings and struck out two batters,[12] at the plate he collected his first major league hit.[11] A few days later, on July 3 he pitched a complete game victory for his first major league start, in the start he struck out nine batters but also walked nine.[12] It was after this start that Rickey decided to transition Sisler to first base.[13] On August 29, Sisler defeated Walter Johnson in a complete game 2–1 victory.[14][15] In 1916 Sisler transitioned fully to first base and played the position for 141 games.[1] His .305 batting average led the team, as did his hits (177), his 24 errors that year led the American League for first basemen.[1]

On August 11, 1917, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics, Sisler recorded three hits in four at bats. Over the next 26 games he would record at least one hit and bat .422 throughout his 26 game hit streak.[16][17] Sisler led the team in most offensive categories[18] and his .353 batting average was second in the American League, behind Ty Cobb.[1] The Selective Service Act of 1917 was passed in May of 1917, and with it, the draft was enacted in the offseason. Sisler\'s teammates Urban Shocker and Ken Williams were assigned Class 1 in the draft, placing them at the top of the draft eligibility list. Williams would only play two games in the 1918 season before being drafted. Sisler was listed as Class 4 much further down on the list. He then enlisted in the army, joining several major league players in a Chemical Warfare Service unit commanded by Rickey. In 1918 he only played in 114 games but was able to steal 45 bases, which led the league, and placed third in the American league with a .341 batting average.[1] Sisler was preparing to go overseas when World War I ended that November.[19]1921 baseball card of SislerIn 1920, Sisler played every inning of each game.[20] He stole 42 bases (second in the American League), collected a major league-leading 257 hits for an average of .407 and ended the season by hitting .442 in August and .448 in September.[1] His batting average was the highest ever for a 600+ at-bat performance. In breaking Ty Cobb\'s 1911 record for hits in a single season, Sisler established a mark which stood until Ichiro Suzuki broke the record with 262 hits in 2004. (Suzuki, however, collected his hits over 161 games during the modern 162-game season as opposed to 154 in Sisler\'s era. Suzuki with 704 at bats to Sisler\'s 631.) Sisler finished second in the AL in doubles and triples, as well as second to Babe Ruth in RBIs and home runs.

Jim Barrero of the Los Angeles Times asserts that Sisler\'s record was largely overshadowed by Ruth\'s 54 home runs that season. \"Of course, Ruth\'s obliteration of the home run record drew all the attention from fans and newspapermen, while Sisler\'s mark was pushed to the side and perhaps left unappreciated during what was a golden age of pure hitters\", Barrero wrote.[20] As his popularity increased, Sisler drew comparisons to Cobb, Ruth and Tris Speaker. Sisler, however, was much more reserved than those three stars. Writer Floyd Bell described Sisler as \"modest, almost to a point of bashfulness, as far from egotism as a blushing debutante... Shift the conversation to Sisler himself and he becomes a clam.\"[21]

In 1922, Sisler hit safely in 41 consecutive games, an American League record that stood until Joe DiMaggio broke it in 1941. His .420 batting average is the third-highest of the 20th century, surpassed only by Nap Lajoie\'s .426 in 1901 and Rogers Hornsby\'s .424 in 1924. Sisler also led the AL in hits (246), runs (134), stolen bases (51), and triples (18). He was chosen as the AL\'s Most Valuable Player that year,[1] the first year an official league award was given, as the Browns finished second to the New York Yankees. Sisler\'s 1922 season is considered by many historians to be among the best individual all-around single-season performances in baseball history.[22]

A severe attack of sinusitis caused him double vision in 1923, forcing him to miss the entire season. He defied some predictions by returning in 1924 with a batting average over .300. Sisler later said, \"I planned to get back in uniform for 1924. I just had to meet a ball with a good swing again, and then run. The doctors all said I\'d never play again, but when you\'re fighting for something that actually keeps you alive – well, the human will is all you need.\"[7] Sisler never regained his previous level of play, though he continued to hit over .300 in six of his last seven seasons and led the AL in stolen bases for a fourth time in 1927.[1]

In 1928, the Browns sold Sisler\'s contract to the Washington Senators, who in turn sold the contract to the Boston Braves in May. After batting .340, .326, and .309 in his three years in Boston, he ended his major league career with the Braves in 1930, then played in the minor leagues.

Sisler accumulated a .340 lifetime batting average over his 16 years in the majors and stole 375 bases during his career. He had 200+ hits in six seasons. He hit over .300 thirteen times, including two seasons in which he hit over .400; 1926 was the only full season in which Sisler\'s average was less than .300. He stole over 25 bases in every year from 1916 through 1922, peaking with 51 the last year and leading the league three times. Sisler holds team records (for the St. Louis Browns, and now the Orioles) for career batting average, triples, and stolen bases, as well as batting average, on-base percentage, hits, on-base plus slugging, and total bases in a season. In 1939, Sisler became one of the first entrants elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.[1] He also posted a career pitching record of 5–6 with a 2.35 earned run average in 24 career appearances.[1] He defeated Walter Johnson twice in complete-game victories.

Later life and legacyAfter his playing career, Sisler reunited with Rickey as a special assignment scout and front-office aide with the St. Louis Cardinals, Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates. Sisler and Rickey worked with future Hall of Famer Duke Snider to teach the young Dodgers hitter to accurately judge the strike zone.[23] Sisler was part of a scouting corps that Rickey assigned to look for black players, though the scouts thought they were looking for players to fill an all-black baseball team separate from MLB. Sisler evaluated Jackie Robinson as a potential star second baseman, but he was concerned about whether Robinson had enough arm strength to play shortstop.[24] With the Pirates in 1961, Sisler had Roberto Clemente switch to a heavier bat. Clemente won the league batting title that season.[25]

Sisler\'s sons Dick and Dave were also major league players in the 1950s. Sisler was a Dodgers scout in 1950 when his son Dick hit a game-winning home run against Brooklyn to clinch the pennant for the Phillies and eliminate the second-place Dodgers. When asked after the pennant winning game how he felt when his son beat his current team, the Dodgers, George replied, \"I felt awful and terrific at the same time.\"[26] A passage in The Old Man and the Sea refers to Dick Sisler\'s long home run drives.[25] Another son, George Jr., served as a minor league executive and as the president of the International League.

Sisler also spent some time as commissioner of the National Baseball Congress.[27] He died in Richmond Heights, Missouri, in 1973, while still employed as a scout for the Pirates.

In 1999 editors at The Sporting News ranked Sisler 33rd on their list of \"Baseball\'s 100 Greatest Players\". Outside of St. Louis\' Busch Stadium, there is a statue honoring Sisler. He is also honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[28] In October 2004, Ichiro Suzuki broke Sisler\'s 84 year old hit record, collecting his 258th hit off of Texas Rangers pitcher Ryan Drese. Sisler\'s daughter Frances (Sisler) Drochelman and other members of his family were in attendance when the record was broken.[29] While in St. Louis for the 2009 All-Star game, Ichiro Suzuki visited Sisler\'s grave site.[30] Tarpon Springs, Florida honored George by naming the former spring training home of the St. Louis Browns \"Sisler Field\". The fields were later taken over by the local Little League teams, and are still in use.[31]

George Sisler was highly thought of as both a person and a ballplayer during his day. A five-tool player before the term came into vogue, Sisler finished his career as one of the game’s greatest hitters.

After graduating with a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Michigan in 1915, a rarity for ball-players at the time, Sisler moved right onto the roster of the St. Louis Browns. Starting his career as a pitcher, he eventually became a first baseman in order to get his powerful left-handed bat in the everyday lineup.

Peerless defensively at first, Sisler also excelled with his 42-ounce bat in hand. In a big league career that lasted 15 seasons, “Gorgeous George” batted over .300 13 times, including league-leading averages of .407 in 1920 and .420 in 1922. His 257 hits during the 1920 campaign remained a modern major league record until Seattle’s Ichiro Suzuki broke it in 2004. A skilled base runner as well, he led the league in stolen bases four times.

Baseball great Ty Cobb, an American League rival for many years, once called Sisler “the nearest thing to a perfect ballplayer” he had ever seen.

Sisler claimed that the fact he was once a pitcher helped make him a better hitter. “I used to stand on the mound myself, study the batter and wonder how I could fool him,” he said. “Now when I am at the plate, I can the more easily place myself in the pitcher’s position and figure what is pass-ing through his mind.”

At the height of his success as a baseball player, though, he missed the entire 1923 season due to a sinus infection that produced double vision. He would come back to play another seven seasons, hitting .320 during that span, but even he would acknowledge he was never quite the same hitter.

Ending his career with 2,812 hits and a .340 batting aver-age, Sisler was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939. But because he often played on second-division teams and never had the national stage of a World Series, he was reserved and much less flamboyant that fellow stars of the time like Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, and as a first baseman was overshadowed by the enormity of Lou Gehrig.

Arguably the first great first baseman of the twentieth century, George Sisler was the greatest player in St. Louis Browns history. An excellent baserunner and superb fielder who was once tried out at second and third base even though he threw left-handed, Sisler\'s primary asset was his left-handed swing, which he used to notch a career .340 batting average. From 1916 to 1925, Sisler batted over .300 nine consecutive times, including two seasons in which he batted better than .400, making him one of only two players in American League history (the other was Ty Cobb) to post multiple .400 batting marks. Though Sisler\'s greatest feats occurred in the years immediately following the end of the Deadball Era, by 1919 he had already established himself as one of the game\'s top young stars, placing in the top three in batting average every year from 1917 to 1919, and leading the league with 45 stolen bases in 1918. That year one writer declared that Sisler possessed \"dazzling ability of the Cobbesque type. He is just as fast, showy, and sensational, very nearly if not quite as good as a natural hitter, as fast in speed of foot, an even better fielder, and gifted with a versatility Cobb himself might envy.\"

George Harold Sisler was born on March 24, 1893, the youngest of three children of Mary Whipple and Cassius Clay Sisler in Manchester, Ohio, 45 miles south of Cleveland. Like many rural communities of the day, baseball was a passion that united the town. Sisler\'s extended family owned and populated much of the surrounding countryside, and young George quickly gained a reputation as a sterling ballplayer without sacrificing the educational values stressed by his parents, both graduates of nearby Hiram College.

While Sisler excelled on the athletic fields and in the classroom, his life turned as he entered his teenage years. Manchester had no high school, and at age 14 he moved to Akron, Ohio, to live with his brother Bert and advance his education. At Akron High, Sisler played football as a slender end, basketball as a smooth forward, and baseball as a southpaw pitcher noted for his speed and curve ball. Sisler also played on several pickup and semi-pro squads, and the local newspapers soon referred to the handsome boy as \"Gorgeous George.\"

Upon graduating from high school, Sisler followed the wishes of his parents and curbed plans to enter the professional ranks in order to pursue a college education. Rejecting scholarship offers from Penn and Western Reserve, Sisler decided to follow his high school catcher Russ Baer to Michigan. Sisler departed Akron with his sights set on law school, but upon his arrival in Ann Arbor enrolled in the engineering program due to his affinity for math.

With no firm plans to play collegiate baseball, Sisler didn\'t act on the notion until several months after he arrived on campus. By that time, the Wolverines had filled their vacant coaching position with the man who would significantly impact Sisler\'s life, Michigan law school grad Branch Rickey. In the late winter of 1912, the confident freshman reported for baseball tryouts at Waterman Gym. Although the session was only for upperclassmen, Rickey was persuaded by a team member to give the green freshman a chance, and by the end of the session Sisler was regarded as a top performer. Freshmen were not eligible for varsity competition, but by leading the first-year engineering students to the school baseball title over a strong group of junior law students, Sisler made his mark on campus.

Sisler\'s career continued to gather momentum as he pitched in Akron\'s industrial league that summer. He and his older brother Cassius, a catcher, comprised the core of the Babcock and Wilcox Boilerworks company team, and the local press chronicled his strikeout total and mound success. On one memorable Sunday afternoon, with the immortal Cy Young perched behind the plate as umpire, Sisler twirled a no-hitter against the Amherst Grays.

A full-fledged member of the Wolverine varsity nine during his sophomore year, Sisler\'s fast start on the mound was interrupted by arm trouble, but his batting averaged remained around .500 most of the campaign. Rickey left the squad to join the Browns front office after the season, but Michigan finished 22-4-1, and Sisler\'s .445 batting average and pitching success earned him All-America honors. Still plagued by a sore arm, Sisler starred at the plate for Akron\'s B&W team again in the summer of 1913 before turning to famed sports medical professional John \"Bonesetter\" Reese for treatment. Despite a sore arm, the following season Sisler split time between the mound and the outfield, and finished the year with a .451 average. Once again, he was named to the All-America team.

At some point during the summer of 1910, before his senior year in high school, Sisler had signed a contract to play for the Akron Champs of the Ohio & Pennsylvania League. Sisler received no bonus money and never reported to the club, and Lee Fohl\'s Champs eventually sold the contract to Columbus. Acting on a tip from Cubs infielder Solly Hofman, Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss scouted Sisler in a sandlot game in Akron in the summer of 1912, purchased his contract, and insisted that Sisler report to the National League club. The story leaked to the press, and Sisler\'s contract became public knowledge.

Confronted with the problem, Rickey\'s keen mind soon found the loophole. Because Sisler was 17 when he signed, the contract was void without his father\'s signature, and Rickey recognized that immediately. Rickey took the case to the National Commission, and after a protracted battle, Cincinnati owner Garry Herrmann cast the deciding vote on January 9, 1915, granting Sisler free agency upon entering the professional ranks.

Sisler then turned his eyes toward professional baseball, and toward his former mentor, the man he called \"Coach\" for the rest of his life, Branch Rickey. After entertaining an offer from Pittsburgh, Sisler signed with the St. Louis Browns for $300 a month, less than Dreyfuss offered him, though the Browns also paid Sisler a $5,000 bonus. Dreyfuss filed a complaint with the National Commission. At 22 years old, Sisler joined the Browns as a left-handed twirler in 1915. The rookie pitched 15 games that summer for the Browns, starting eight and throwing six complete games. In 70 innings he compiled a 2.83 ERA. While Sisler experienced mound success that summer, it took Rickey only a few days to start working him at first base and the outfield. His hitting came in spurts, but he ended the season with a solid .285 batting average, three homers and 29 RBI. The highlight of his rookie season was a 2-1 win over Walter Johnson on August 29 in which he limited the Senators to six hits and struck out three, winning the game thanks to Del Pratt\'s successful execution of the hidden ball trick. For the remainder of his life, Sisler spoke of that game as his greatest thrill in baseball. \"Sisler can be counted a baseball freak,\" the Washington Post reported the next day. \"[Rickey] plays him in the outfield and he makes sensational catches... he plays him on first base and actually he looks like Hal Chase when Hal was king of the first sackers, and then on the hill he goes out and beats Johnson.\"

St. Louis\' new controlling partner Phil Ball replaced Rickey with Fielder Jones during the 1916 season, but despite the changes Sisler consolidated his hitting gains and took over as the club\'s first baseman. He hit .305, the first of nine straight seasons over .300, and rapped out 11 triples and four homers, as the Browns finished in fifth place with their first winning record in eight years. On June 10, 1916, the National Commission finally issued its ruling on Dreyfuss\'s grievance, turning it down and declaring Sisler\'s contract with St. Louis legitimate.

As war loomed on the national horizon in 1917 the newlywed Sisler, who had married his college sweetheart Kathleen Holznagle the previous fall, became a star. Limited to three mound appearances in 1916, none in 1917, and just two in 1918, Sisler\'s grace around first base drew him accolades as one of the league\'s top defensive players. He was also an offensive star, finishing second in the league in hits, fourth in doubles and fifth in stolen bases in 1917, and third in hits in 1918 with a league-leading 45 steals. The national press took to calling him \"the next Cobb.\"

From 1919 to 1922, Sisler largely fulfilled that promise, as he batted .407 to win his first batting title in 1920, collecting 257 hits, a major league record that would last 84 years. He captured his second batting crown in 1922 with a .420 mark, which still stands as the third-best season average in modern baseball history. After the 1922 season, Sisler was given the inaugural American League Trophy as the league\'s MVP, voted on by a league-appointed panel of sportswriters.

Sisler finished second in the league in stolen bases in 1919 and 1920, and led the league in 1921 and 1922. Though Sisler often ranked among the league leaders in doubles, triples, and home runs, he was primarily a place hitter, adept at finding the gaps in opposing defenses. Like Cobb, Sisler stood erect at the plate, and relied on his superior hand-eye reflexes to react to a pitch\'s location and lash out base hits. \"Except when I cut loose at the ball, I always try to place my hits,\" he once explained. \"At the plate you must stand in such a way that you can hit to either right or left field with equal ease.\" Unlike Cobb, who shifted his feet while hitting, Sisler was an advocate of the flat-footed swing.

At the peak of his powers following his historic 1922 performance, Sisler missed the entire 1923 season with a severe sinus infection that impaired his optic nerve, plaguing him with chronic headaches and double vision. Though he was able to return to the field in 1924, when he also agreed to serve as manager of the Browns, Sisler was never again the same player. He batted .305 in 1924--below the league average--improved to .345 the following year, but then batted just .290 in 1926 with a .398 slugging percentage. Under his management, the Browns finished fourth in 1924 and third a year later. After falling to seventh place in 1926, Sisler was removed as manager, and later admitted that he \"wasn\'t ready\" for the post. In 1927, his last season with the Browns, he hit .327 and knocked out 201 hits. He was shipped to Washington before the 1928 season, but was traded to the Boston Braves early in the campaign. He finished his major league career in strong fashion, hitting .326 in 1929 and .309 in \'30.

After spending the 1931 campaign with Rochester of the International League and 1932 with Shreveport-Tyler of the Texas League, Sisler retired from baseball. He launched several private ventures, including a sporting goods company, and founded the American Softball Association. Sisler engineered the first lighted softball park, and that sport boomed throughout the 1930s. In 1939, Sisler was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the writers\' panel, and was among the first four classes of inductees enshrined that summer.

In 1942, Branch Rickey hired the 49-year-old Sisler to scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Sisler served in this capacity throughout the decade, but his greatest contribution may have come in preparing Jackie Robinson to break baseball\'s color barrier. He scouted Robinson prior to his signing with the Dodgers, and helped the future Hall of Famer make the transition to first base during his first year in the majors. Sisler moved to Brooklyn to assume an expanded role with the Dodgers in 1947, and in addition to scouting and player development helped tutor several of the players that would serve as the foundation of the outstanding Dodgers teams of the 1950s. When Rickey moved to the Pirates before the 1951 season, Sisler again went with him. There he helped bring Bill Mazeroski into the fold, and also worked with Roberto Clemente, teaching him to keep his head still during his swing.

Sisler remained with the Pirates after Rickey left, but after serious abdominal surgery in 1957 he and Kathleen moved back to St. Louis. Despite the move, Sisler remained with the Pirates as a roving hitting coach, and instructed such players as Willie Stargell, Gene Alley, and Donn Clendenon. Sisler passed away on March 26, 1973, in Richmond Heights, Missouri. Kathleen survived him by 17 years. The couple had three sons, one of whom, Dick Sisler, spent eight years in the major leagues and later managed the Cincinnati Reds. Another son, Dave Sisler, had a seven-year career as a big league pitcher. George Sisler is buried at the Old Meeting House Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Frontenac, Missouri.

George Harold Sisler (March 24, 1893 - March 26, 1973), nicknamed \"Gorgeous George,\" was an American star left-handed first basemen in Major League Baseball (MLB). Ty Cobb called him \"the nearest thing to a perfect ballplayer.\" He is widely regarded as having been one of the greatest players in St. Louis Browns history and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.

Although his career ended in 1930, from 1920 until 2004, Sisler held the MLB record for most hits in a single season. He is also one of only three men (along with Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby) since 1900 to have a batting average over .400 more than once. In the 1920s, a team\'s typical baseball season was 152 games, without including World Series games.Contents1 Early life2 Career3 Legacy4 Notes5 References6 External links7 CreditsAn unheralded superstar of the 1920s, he was a versatile player: Initially a pitcher, he became a dazzling hitter (.340 lifetime average, batting over .400 twice) who later became an excellent first baseman and he was also a threat as a base stealer (he lead the league four times). He was one of the first 10 to to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame (1939). Afterward, he moved into management, and scouted (and gave batting training to) Jackie Robinson.Early lifeSisler was born in the unincorporated hamlet of Manchester, Ohio, which is about 12 miles south of Akron, in Summit County, to Cassius Sisler and Mary Whipple. They were both graduates of Hiram College and he had an uncle who was the mayor of Akron.

He played college ball for coach Branch Rickey at the University of Michigan, where he earned a degree in mechanical engineering. By 1915, as a senior, he was the outstanding college player in the country. He turned down a salary offer for $5,200 from Pittsburgh and signed with the Browns for $7,400.[2]

Sisler came into the major leagues as a pitcher for the St. Louis Browns in 1915. He signed as a free agent after the minor league contract he had signed as a minor four years earlier, and which the Pittsburgh Pirates had purchased, was declared void. The following year he switched to first base; like Babe Ruth, he was too good a hitter to be limited to hitting once every four days. He posted a record of 5-6 with a 2.35 earned run average in 24 career mound appearances, twice defeating Walter Johnson in complete game victories.

In 1918 Sisler joined the Chemical Corps (known at that time as the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) during World War I. He was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to Camp Humphries, Virginia. Also with CWS were Branch Rickey, Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, and Perry Haughton (president of the Boston Bravces) were sent to France. Just as Sisler was preparing to deploy overseas, the armistice was signed on November 11. Sisler was subsequently discharged from the CWS.[3]CareerBaseball Hall of FameGeorge Sisleris a member ofBaseballHall of FameIn 1920, Sisler had a dream year. He not only played every inning of every game that season, but stole 42 bases (second in the American League), collected 257 hits for an average of .407, and ended the season by hitting .442 in August and .448 in September. In breaking Cobb\'s 1911 record for hits in a single season, Sisler established a mark that wasn\'t broken until 2004. In addition, Sisler finished second in the American League (AL) that year in doubles and triples, as well as second to Babe Ruth in RBIs and homers.

Sisler did even better in 1922, hitting safely in 41 consecutive games—an American League record that stood until Joe DiMaggio broke it in 1941. His .420 batting average is the third-highest of the twentieth century, surpassed only by Rogers Hornsby\'s .424 in 1924, and Nap Lajoie\'s .426 in 1901. He was chosen as the AL\'s Most Valuable Player that year, the first year an official league award was given. One of the rare first basemen who were also a threat on the basepaths, Sisler stole over 25 bases in every year from 1916 to 1922, peaking with 51 the last year and leading the league three times; he also scored an AL-best 134 runs, and hit 18 triples for the third year in a row.1915 M101-5 George SislerIn 1923, a severe attack of sinusitis caused him to see double, forcing him to miss the entire season. The inflamed sinuses put pressure on his eyes, and surgery was required. The surgery was performed in April, but Sisler had to wear dark glasses through the summer, and afterwards he always squinted to keep the light affecting his eyes at a minimum. Frustrated at the slow pace of recovery, Sisler began to blame his doctors for his condition, and he embraced Christian Science.[4]

In 1924, the veteran Sisler was back, having inked a deal to play and manage the team. The managerial responsibility and the lingering affects of sinusitis limited George to a .305 average in 151 games. The club finished with an identical record as it had posted the previous season. He managed the team for two more years, guiding the Browns to a third place finish in 1925, and 92 losses in 1926, before he resigned. In 1925, Sisler regained some of his batting luster, hitting .345 with 224 hits, but in \'26, he hit a disappointing .290 in 150 games.

Sisler came into the 1927 season free of managerial responsibility. After a strong start, he tapered off, but still managed 201 hits, a .327 average, 97 runs batted in and led the AL in stolen bases for a fourth time. Even though he was 34 years old and his legs were beaten from years of punishment, Sisler\'s 7 stolen bases led the league. After Heinie Manush and Lu Blue (a switch-hitting first baseman) were acquired in a blockbuster deal in early December, Sisler was sold to the Washington Senators in a move extremely unpopular with St. Louis fans. He played just over a month with Washington, where he hit .245, before he was shipped to the Boston Braves. In his first look at National League pitching, Sisler hit a robust .340 with 167 hits in 118 games. That earned him two more seasons in the Hub City, where he hit .326 in 1929, and .309 in 1930.[5] In 1928, the St. Louis Browns sold Sisler\'s contract to the Washington Senators, who in turn sold the contract to the Boston Braves in May. After batting .340, .326 and .309 in his three years in Boston, he ended his major league career with the Braves in 1930, then played in the minor leagues.n 1931, nearing his 38th birthday and receiving no offers from big league clubs, Sisler signed with Rochester of the International League. In 159 games for Rochester, Sisler batted .303. The following year, he took an assignment as manager of Shreveport/Tyler of the Texas League, finding time to play in 70 games and hit .287 with 17 steals at the age of 39. Sisler then retired as a manager and player.

Sisler posted a .340 lifetime batting mark in the big leagues, led the league in assists six times as a first baseman, and in putouts several times as well. He collected 2,812 hits, 425 doubles, 164 triples, 102 homers, 1,175 RBI, and 375 stolen bases. He had struck out only 327 times in his 15-year career. His abbreviated pitching mark stood at 5-6 with a 2.35 ERA in 111 innings.[6]

George Sisler died in Richmond Heights, Missouri, at age 80.

LegacySisler\'s legacy was confirmed in 1999, when two significant polls were conducted. That year, Sisler received the 8th most votes of any First Baseman in the poll for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, a poll voted on by fans. Also in 1999, editors at the The Sporting News named Sisler the 33rd best player on their list of Baseball\'s 100 Greatest Players.

Sisler\'s sons, Dick and Dave, were also major league players in the 1950s; another son, George Jr., was played in the minor leagues and later was the International League president.

It was 84 years before Ichiro Suzuki broke Sisler\'s record for hits in a season by getting 262 hits over the modern 162 game schedule.

The greatest player in St. Louis Browns history, “Gentleman” George Sisler was arguably baseball’s most complete first baseman. Intelligent and athletic, he won two batting titles, led the league in steals four times and was one of the finest fielders ever. In 1920 he batted .407 and his 257 hits set a record that stood until 2004. League MVP in 1922, “The Sizzler” hit .420 and heroically led the mediocre Browns to within a game of the pennant. He finished his career with a .340 average and lived the rest of his life in St. Louis. Elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939, George Sisler was described by Ty Cobb as “the nearest thing to a perfect ballplayer.”Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding team, called the pitcher, throws a ball that a player on the batting team, called the batter, tries to hit with a bat. The objective of the offensive team (batting team) is to hit the ball into the field of play, away from the other team\'s players, allowing its players to run the bases, having them advance counter-clockwise around four bases to score what are called \"runs\". The objective of the defensive team (referred to as the fielding team) is to prevent batters from becoming runners, and to prevent runners\' advance around the bases.[2] A run is scored when a runner legally advances around the bases in order and touches home plate (the place where the player started as a batter).

The principal objective of the batting team is to have a player reach first base safely; this generally occurs either when the batter hits the ball and reaches first base before an opponent retrieves the ball and touches the base, or when the pitcher persists in throwing the ball out of the batter\'s reach. Players on the batting team who reach first base without being called \"out\" can attempt to advance to subsequent bases as a runner, either immediately or during teammates\' turns batting. The fielding team tries to prevent runs by getting batters or runners \"out\", which forces them out of the field of play. The pitcher can get the batter out by throwing three pitches which result in strikes, while fielders can get the batter out by catching a batted ball before it touches the ground, and can get a runner out by tagging them with the ball while the runner is not touching a base.

The opposing teams switch back and forth between batting and fielding; the batting team\'s turn to bat is over once the fielding team records three outs. One turn batting for each team constitutes an inning. A game is usually composed of nine innings, and the team with the greater number of runs at the end of the game wins. Most games end after the ninth inning, but if scores are tied at that point, extra innings are usually played. Baseball has no game clock, though some competitions feature pace-of-play regulations such as the pitch clock to shorten game time.

Baseball evolved from older bat-and-ball games already being played in England by the mid-18th century. This game was brought by immigrants to North America, where the modern version developed. Baseball\'s American origins, as well as its reputation as a source of escapism during troubled points in American history such as the American Civil War and the Great Depression, have led the sport to receive the moniker of \"America\'s Pastime\"; since the late 19th century, it has been unofficially recognized as the national sport of the United States, though in modern times is considered less popular than other sports, such as American football. In addition to North America, baseball is considered the most popular sport in parts of Central and South America, the Caribbean, and East Asia, particularly in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

In Major League Baseball (MLB), the highest level of professional baseball in the United States and Canada, teams are divided into the National League (NL) and American League (AL), each with three divisions: East, West, and Central. The MLB champion is determined by playoffs that culminate in the World Series. The top level of play is similarly split in Japan between the Central and Pacific Leagues and in Cuba between the West League and East League. The World Baseball Classic, organized by the World Baseball Softball Confederation, is the major international competition of the sport and attracts the top national teams from around the world. Baseball was played at the Olympic Games from 1992 to 2008, and was reinstated in 2020.

Rules and gameplayFurther information: Baseball rules and Outline of baseball

Diagram of a baseball field Diamond may refer to the square area defined by the four bases or to the entire playing field. The dimensions given are for professional and professional-style games. Children often play on smaller fields.

2013 World Baseball Classic championship match between the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, March 20, 2013A baseball game is played between two teams, each usually composed of nine players, that take turns playing offense (batting and baserunning) and defense (pitching and fielding). A pair of turns, one at bat and one in the field, by each team constitutes an inning. A game consists of nine innings (seven innings at the high school level and in doubleheaders in college, Minor League Baseball and, since the 2020 season, Major League Baseball; and six innings at the Little League level).[3] One team—customarily the visiting team—bats in the top, or first half, of every inning. The other team—customarily the home team—bats in the bottom, or second half, of every inning. The goal of the game is to score more points (runs) than the other team. The players on the team at bat attempt to score runs by touching all four bases, in order, set at the corners of the square-shaped baseball diamond. A player bats at home plate and must attempt to safely reach a base before proceeding, counterclockwise, from first base, to second base, third base, and back home to score a run. The team in the field attempts to prevent runs from scoring by recording outs, which remove opposing players from offensive action, until their next turn at bat comes up again. When three outs are recorded, the teams switch roles for the next half-inning. If the score of the game is tied after nine innings, extra innings are played to resolve the contest. Many amateur games, particularly unorganized ones, involve different numbers of players and innings.[4]

The game is played on a field whose primary boundaries, the foul lines, extend forward from home plate at 45-degree angles. The 90-degree area within the foul lines is referred to as fair territory; the 270-degree area outside them is foul territory. The part of the field enclosed by the bases and several yards beyond them is the infield; the area farther beyond the infield is the outfield. In the middle of the infield is a raised pitcher\'s mound, with a rectangular rubber plate (the rubber) at its center. The outer boundary of the outfield is typically demarcated by a raised fence, which may be of any material and height. The fair territory between home plate and the outfield boundary is baseball\'s field of play, though significant events can take place in foul territory, as well.[5]

There are three basic tools of baseball: the ball, the bat, and the glove or mitt:

The baseball is about the size of an adult\'s fist, around 9 inches (23 centimeters) in circumference. It has a rubber or cork center, wound in yarn and covered in white cowhide, with red stitching.[6]The bat is a hitting tool, traditionally made of a single, solid piece of wood. Other materials are now commonly used for nonprofessional games. It is a hard round stick, about 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) in diameter at the hitting end, tapering to a narrower handle and culminating in a knob. Bats used by adults are typically around 34 inches (86 centimeters) long, and not longer than 42 inches (110 centimeters).[7]The glove or mitt is a fielding tool, made of padded leather with webbing between the fingers. As an aid in catching and holding onto the ball, it takes various shapes to meet the specific needs of different fielding positions.[8]Protective helmets are also standard equipment for all batters.[9]

At the beginning of each half-inning, the nine players of the fielding team arrange themselves around the field. One of them, the pitcher, stands on the pitcher\'s mound. The pitcher begins the pitching delivery with one foot on the rubber, pushing off it to gain velocity when throwing toward home plate. Another fielding team player, the catcher, squats on the far side of home plate, facing the pitcher. The rest of the fielding team faces home plate, typically arranged as four infielders—who set up along or within a few yards outside the imaginary lines (basepaths) between first, second, and third base—and three outfielders. In the standard arrangement, there is a first baseman positioned several steps to the left of first base, a second baseman to the right of second base, a shortstop to the left of second base, and a third baseman to the right of third base. The basic outfield positions are left fielder, center fielder, and right fielder. With the exception of the catcher, all fielders are required to be in fair territory when the pitch is delivered. A neutral umpire sets up behind the catcher.[10] Other umpires will be distributed around the field as well.[11]David Ortiz, the batter, awaiting a pitch, with the catcher and umpirePlay starts with a member of the batting team, the batter, standing in either of the two batter\'s boxes next to home plate, holding a bat.[12] The batter waits for the pitcher to throw a pitch (the ball) toward home plate, and attempts to hit the ball[13] with the bat.[12] The catcher catches pitches that the batter does not hit—as a result of either electing not to swing or failing to connect—and returns them to the pitcher. A batter who hits the ball into the field of play must drop the bat and begin running toward first base, at which point the player is referred to as a runner (or, until the play is over, a batter-runner). A batter-runner who reaches first base without being put out is said to be safe and is on base. A batter-runner may choose to remain at first base or attempt to advance to second base or even beyond—however far the player believes can be reached safely. A player who reaches base despite proper play by the fielders has recorded a hit. A player who reaches first base safely on a hit is credited with a single. If a player makes it to second base safely as a direct result of a hit, it is a double; third base, a triple. If the ball is hit in the air within the foul lines over the entire outfield (and outfield fence, if there is one), or if the batter-runner otherwise safely circles all the bases, it is a home run: the batter and any runners on base may all freely circle the bases, each scoring a run. This is the most desirable result for the batter. The ultimate and most desirable result possible for a batter would be to hit a home run while all three bases are occupied or \"loaded\", thus scoring four runs on a single hit. This is called a grand slam. A player who reaches base due to a fielding mistake is not credited with a hit—instead, the responsible fielder is charged with an error.[12]

Any runners already on base may attempt to advance on batted balls that land, or contact the ground, in fair territory, before or after the ball lands. A runner on first base must attempt to advance if a ball lands in play, as only one runner may occupy a base at any given time. If a ball hit into play rolls foul before passing through the infield, it becomes dead and any runners must return to the base they occupied when the play began. If the ball is hit in the air and caught before it lands, the batter has flied out and any runners on base may attempt to advance only if they tag up (contact the base they occupied when the play began, as or after the ball is caught). Runners may also attempt to advance to the next base while the pitcher is in the process of delivering the ball to home plate; a successful effort is a stolen base.[14]

A pitch that is not hit into the field of play is called either a strike or a ball. A batter against whom three strikes are recorded strikes out. A batter against whom four balls are recorded is awarded a base on balls or walk, a free advance to first base. (A batter may also freely advance to first base if the batter\'s body or uniform is struck by a pitch outside the strike zone, provided the batter does not swing and attempts to avoid being hit.)[15] Crucial to determining balls and strikes is the umpire\'s judgment as to whether a pitch has passed through the strike zone, a conceptual area above home plate extending from the midpoint between the batter\'s shoulders and belt down to the hollow of the knee.[16] Any pitch which does not pass through the strike zone is called a ball, unless the batter either swings and misses at the pitch, or hits the pitch into foul territory; an exception generally occurs if the ball is hit into foul territory when the batter already has two strikes, in which case neither a ball nor a strike is called.A shortstop tries to tag out a runner who is sliding head first, attempting to reach second base.While the team at bat is trying to score runs, the team in the field is attempting to record outs. In addition to the strikeout and flyout, common ways a member of the batting team may be put out include the ground out, force out, and tag out. These occur either when a runner is forced to advance to a base, and a fielder with possession of the ball reaches that base before the runner does, or the runner is touched by the ball, held in a fielder\'s hand, while not on a base. (The batter-runner is always forced to advance to first base, and any other runners must advance to the next base if a teammate is forced to advance to their base.) It is possible to record two outs in the course of the same play. This is called a double play. Three outs in one play, a triple play, is possible, though rare. Players put out or retired must leave the field, returning to their team\'s dugout or bench. A runner may be stranded on base when a third out is recorded against another player on the team. Stranded runners do not benefit the team in its next turn at bat as every half-inning begins with the bases empty.[17]

An individual player\'s turn batting or plate appearance is complete when the player reaches base, hits a home run, makes an out, or hits a ball that results in the team\'s third out, even if it is recorded against a teammate. On rare occasions, a batter may be at the plate when, without the batter\'s hitting the ball, a third out is recorded against a teammate—for instance, a runner getting caught stealing (tagged out attempting to steal a base). A batter with this sort of incomplete plate appearance starts off the team\'s next turn batting; any balls or strikes recorded against the batter the previous inning are erased. A runner may circle the bases only once per plate appearance and thus can score at most a single run per batting turn. Once a player has completed a plate appearance, that player may not bat again until the eight other members of the player\'s team have all taken their turn at bat in the batting order. The batting order is set before the game begins, and may not be altered except for substitutions. Once a player has been removed for a substitute, that player may not reenter the game. Children\'s games often have more lenient rules, such as Little League rules, which allow players to be substituted back into the same game.[3][18]

If the designated hitter (DH) rule is in effect, each team has a tenth player whose sole responsibility is to bat (and run). The DH takes the place of another player—almost invariably the pitcher—in the batting order, but does not field. Thus, even with the DH, each team still has a batting order of nine players and a fielding arrangement of nine players.[19]

PersonnelSee also: Baseball positionsPlayers

Defensive positions on a baseball field, with abbreviations and scorekeeper\'s position numbers (not uniform numbers)See also the categories Baseball players and Lists of baseball playersThe number of players on a baseball roster, or squad, varies by league and by the level of organized play. A Major League Baseball (MLB) team has a roster of 26 players with specific roles. A typical roster features the following players:[20]

Eight position players: the catcher, four infielders, and three outfielders—all of whom play on a regular basisFive starting pitchers who constitute the team\'s pitching rotation or starting rotationSeven relief pitchers, including one closer, who constitute the team\'s bullpen (named for the off-field area where pitchers warm up)One backup, or substitute, catcherFive backup infielders and backup outfielders, or players who can play multiple positions, known as utility players.Most baseball leagues worldwide have the DH rule, including MLB, Japan\'s Pacific League, and Caribbean professional leagues, along with major American amateur organizations.[21] The Central League in Japan does not have the rule and high-level minor league clubs connected to National League teams are not required to field a DH.[22] In leagues that apply the designated hitter rule, a typical team has nine offensive regulars (including the DH), five starting pitchers,[23] seven or eight relievers, a backup catcher, and two or three other reserve players.[24][25]

Managers and coachesThe manager, or head coach, oversees the team\'s major strategic decisions, such as establishing the starting rotation, setting the lineup, or batting order, before each game, and making substitutions during games—in particular, bringing in relief pitchers. Managers are typically assisted by two or more coaches; they may have specialized responsibilities, such as working with players on hitting, fielding, pitching, or strength and conditioning. At most levels of organized play, two coaches are stationed on the field when the team is at bat: the first base coach and third base coach, who occupy designated coaches\' boxes, just outside the foul lines. These coaches assist in the direction of baserunners, when the ball is in play, and relay tactical signals from the manager to batters and runners, during pauses in play.[26] In contrast to many other team sports, baseball managers and coaches generally wear their team\'s uniforms; coaches must be in uniform to be allowed on the field to confer with players during a game.[27]

UmpiresAny baseball game involves one or more umpires, who make rulings on the outcome of each play. At a minimum, one umpire will stand behind the catcher, to have a good view of the strike zone, and call balls and strikes. Additional umpires may be stationed near the other bases, thus making it easier to judge plays such as attempted force outs and tag outs. In MLB, four umpires are used for each game, one near each base. In the playoffs, six umpires are used: one at each base and two in the outfield along the foul lines.[28]

StrategySee also: Baseball positioningMany of the pre-game and in-game strategic decisions in baseball revolve around a fundamental fact: in general, right-handed batters tend to be more successful against left-handed pitchers and, to an even greater degree, left-handed batters tend to be more successful against right-handed pitchers.[29] A manager with several left-handed batters in the regular lineup, who knows the team will be facing a left-handed starting pitcher, may respond by starting one or more of the right-handed backups on the team\'s roster. During the late innings of a game, as relief pitchers and pinch hitters are brought in, the opposing managers will often go back and forth trying to create favorable matchups with their substitutions. The manager of the fielding team trying to arrange same-handed pitcher-batter matchups and the manager of the batting team trying to arrange opposite-handed matchups. With a team that has the lead in the late innings, a manager may remove a starting position player—especially one whose turn at bat is not likely to come up again—for a more skillful fielder (known as a defensive substitution).[30]

TacticsPitching and fielding

A first baseman receives a pickoff throw, as the runner dives back to first base.See also: Pitch (baseball)The tactical decision that precedes almost every play in a baseball game involves pitch selection.[31] By gripping and then releasing the baseball in a certain manner, and by throwing it at a certain speed, pitchers can cause the baseball to break to either side, or downward, as it approaches the batter, thus creating differing pitches that can be selected.[32] Among the resulting wide variety of pitches that may be thrown, the four basic types are the fastball, the changeup (or off-speed pitch), and two breaking balls—the curveball and the slider.[33] Pitchers have different repertoires of pitches they are skillful at throwing. Conventionally, before each pitch, the catcher signals the pitcher what type of pitch to throw, as well as its general vertical and/or horizontal location.[34] If there is disagreement on the selection, the pitcher may shake off the sign and the catcher will call for a different pitch.

With a runner on base and taking a lead, the pitcher may attempt a pickoff, a quick throw to a fielder covering the base to keep the runner\'s lead in check or, optimally, effect a tag out.[35] Pickoff attempts, however, are subject to rules that severely restrict the pitcher\'s movements before and during the pickoff attempt. Violation of any one of these rules could result in the umpire calling a balk against the pitcher, which permits any runners on base to advance one base with impunity.[36] If an attempted stolen base is anticipated, the catcher may call for a pitchout, a ball thrown deliberately off the plate, allowing the catcher to catch it while standing and throw quickly to a base.[37] Facing a batter with a strong tendency to hit to one side of the field, the fielding team may employ a shift, with most or all of the fielders moving to the left or right of their usual positions. With a runner on third base, the infielders may play in, moving closer to home plate to improve the odds of throwing out the runner on a ground ball, though a sharply hit grounder is more likely to carry through a drawn-in infield.[38]

Batting and baserunningSeveral basic offensive tactics come into play with a runner on first base, including the fundamental choice of whether to attempt a steal of second base. The hit and run is sometimes employed, with a skillful contact hitter, the runner takes off with the pitch, drawing the shortstop or second baseman over to second base, creating a gap in the infield for the batter to poke the ball through.[39] The sacrifice bunt, calls for the batter to focus on making soft contact with the ball, so that it rolls a short distance into the infield, allowing the runner to advance into scoring position as the batter is thrown out at first. A batter, particularly one who is a fast runner, may also attempt to bunt for a hit. A sacrifice bunt employed with a runner on third base, aimed at bringing that runner home, is known as a squeeze play.[40] With a runner on third and fewer than two outs, a batter may instead concentrate on hitting a fly ball that, even if it is caught, will be deep enough to allow the runner to tag up and score—a successful batter, in this case, gets credit for a sacrifice fly.[38] In order to increase the chance of advancing a batter to first base via a walk, the manager will sometimes signal a batter who is ahead in the count (i.e., has more balls than strikes) to take, or not swing at, the next pitch. The batter\'s potential reward of reaching base (via a walk) exceeds the disadvantage if the next pitch is a strike.[41]

HistoryMain article: History of baseballFurther information: Origins of baseballThe evolution of baseball from older bat-and-ball games is difficult to trace with precision. Consensus once held that today\'s baseball is a North American development from the older game rounders, popular among children in Great Britain and Ireland.[42][43][44] American baseball historian David Block suggests that the game originated in England; recently uncovered historical evidence supports this position. Block argues that rounders and early baseball were actually regional variants of each other, and that the game\'s most direct antecedents are the English games of stoolball and \"tut-ball\".[42] The earliest known reference to baseball is in a 1744 British publication, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, by John Newbery.[45] Block discovered that the first recorded game of \"Bass-Ball\" took place in 1749 in Surrey, and featured the Prince of Wales as a player.[46] This early form of the game was apparently brought to Canada by English immigrants.[47]

By the early 1830s, there were reports of a variety of uncodified bat-and-ball games recognizable as early forms of baseball being played around North America.[48] The first officially recorded baseball game in North America was played in Beachville, Ontario, Canada, on June 4, 1838.[49] In 1845, Alexander Cartwright, a member of New York City\'s Knickerbocker Club, led the codification of the so-called Knickerbocker Rules,[50] which in turn were based on rules developed in 1837 by William R. Wheaton of the Gotham Club.[51] While there are reports that the New York Knickerbockers played games in 1845, the contest long recognized as the first officially recorded baseball game in U.S. history took place on June 19, 1846, in Hoboken, New Jersey: the \"New York Nine\" defeated the Knickerbockers, 23–1, in four innings.[52] With the Knickerbocker code as the basis, the rules of modern baseball continued to evolve over the next half-century.[53] By the time of the Civil War, baseball had begun to overtake its fellow bat-and-ball sport cricket in popularity within the United States, due in part to baseball being of a much shorter duration than the form of cricket played at the time, as well as the fact that troops during the Civil War did not need a specialized playing surface to play baseball, as they would have required for cricket.[54][55]

In the United StatesFurther information: Baseball in the United States and History of baseball in the United StatesEstablishment of professional leaguesIn the mid-1850s, a baseball craze hit the New York metropolitan area,[56] and by 1856, local journals were referring to baseball as the \"national pastime\" or \"national game\".[57] A year later, the sport\'s first governing body, the National Association of Base Ball Players, was formed. In 1867, it barred participation by African Americans.[58] The more formally structured National League was founded in 1876.[59] Professional Negro leagues formed, but quickly folded.[60] In 1887, softball, under the name of indoor baseball or indoor-outdoor, was invented as a winter version of the parent game.[61] The National League\'s first successful counterpart, the American League, which evolved from the minor Western League, was established in 1893, and virtually all of the modern baseball rules were in place by then.[62][63]

The National Agreement of 1903 formalized relations both between the two major leagues and between them and the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues, representing most of the country\'s minor professional leagues.[64] The World Series, pitting the two major league champions against each other, was inaugurated that fall.[65] The Black Sox Scandal of the 1919 World Series led to the formation of the office of the Commissioner of Baseball.[66] The first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, was elected in 1920. That year also saw the founding of the Negro National League; the first significant Negro league, it would operate until 1931. For part of the 1920s, it was joined by the Eastern Colored League.[67]

Rise of Ruth and racial integrationCompared with the present, professional baseball in the early 20th century was lower-scoring, and pitchers were more dominant.[68] The so-called dead-ball era ended in the early 1920s with several changes in rule and circumstance that were advantageous to hitters. Strict new regulations governed the ball\'s size, shape and composition, along with a new rule officially banning the spitball and other pitches that depended on the ball being treated or roughed-up with foreign substances, resulted in a ball that traveled farther when hit.[69] The rise of the legendary player Babe Ruth, the first great power hitter of the new era, helped permanently alter the nature of the game.[70] In the late 1920s and early 1930s, St. Louis Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey invested in several minor league clubs and developed the first modern farm system.[71] A new Negro National League was organized in 1933; four years later, it was joined by the Negro American League. The first elections to the National Baseball Hall of Fame took place in 1936. In 1939, Little League Baseball was founded in Pennsylvania.[72]

Robinson posing in the uniform cap of the Kansas City Royals, a California Winter League barnstorming team, November 1945 (photo by Maurice Terrell)Jackie Robinson in 1945, with the era\'s Kansas City Royals, a barnstorming squad associated with the Negro American League\'s Kansas City MonarchsA large number of minor league teams disbanded when World War II led to a player shortage. Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley led the formation of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League to help keep the game in the public eye.[73] The first crack in the unwritten agreement barring blacks from white-controlled professional ball occurred in 1945: Jackie Robinson was signed by the National League\'s Brooklyn Dodgers and began playing for their minor league team in Montreal.[74] In 1947, Robinson broke the major leagues\' color barrier when he debuted with the Dodgers.[75] Latin-American players, largely overlooked before, also started entering the majors in greater numbers. In 1951, two Chicago White Sox, Venezuelan-born Chico Carrasquel and black Cuban-born Minnie Miñoso, became the first Hispanic All-Stars.[76][77] Integration proceeded slowly: by 1953, only six of the 16 major league teams had a black player on the roster.[76]

Attendance records and the age of steroidsIn 1975, the union\'s power—and players\' salaries—began to increase greatly when the reserve clause was effectively struck down, leading to the free agency system.[78] Significant work stoppages occurred in 1981 and 1994, the latter forcing the cancellation of the World Series for the first time in 90 years.[79] Attendance had been growing steadily since the mid-1970s and in 1994, before the stoppage, the majors were setting their all-time record for per-game attendance.[80][81] After play resumed in 1995, non-division-winning wild card teams became a permanent fixture of the post-season. Regular-season interleague play was introduced in 1997 and the second-highest attendance mark for a full season was set.[82] In 2000, the National and American Leagues were dissolved as legal entities. While their identities were maintained for scheduling purposes (and the designated hitter distinction), the regulations and other functions—such as player discipline and umpire supervision—they had administered separately were consolidated under the rubric of MLB.[83]

In 2001, Barry Bonds established the current record of 73 home runs in a single season. There had long been suspicions that the dramatic increase in power hitting was fueled in large part by the abuse of illegal steroids (as well as by the dilution of pitching talent due to expansion), but the issue only began attracting significant media attention in 2002 and there was no penalty for the use of performance-enhancing drugs before 2004.[84] In 2007, Bonds became MLB\'s all-time home run leader, surpassing Hank Aaron, as total major league and minor league attendance both reached all-time highs.[85][86]